The Queen of the Curve: Designing the Future of Architecture

In the rarified world of architecture, few creators have so effortlessly sculpted a new lexicon of form and space as Dame Zaha Hadid. Her journey was not merely a career but a singular, relentless pursuit of a vision that transcended the conventional and redefined the very essence of the built world. From her formative years in Baghdad to her status as a global icon, Hadid's life was a testament to the power of unyielding imagination, a lived example of what might be called The Art of Being. This comprehensive study explores the life, the inspirations, and the lasting legacy of a pioneer who did not just design structures, but actively shaped the future of culture and aesthetics on a global stage.

The Formative Years: A River of Inspiration

The extraordinary journey of Zaha Hadid began not in the conventional design capitals of the world, but in a cosmopolitan Baghdad, a city that fostered a worldly and unburdened mindset. Born in 1950 into an educated, liberal family, her upbringing was the very crucible of her creative vision. A pivotal childhood journey with her father to the ancient Sumerian cities and the southern Iraqi marshes left an indelible mark on her young mind. She was captivated by a landscape where "sand, water, reeds, birds, buildings, and people all somehow flowed together." This early visual memory of natural, seamless elegance became a subconscious wellspring, a recurring theme that would later manifest in her breathtakingly fluid, curvilinear designs.

Her academic path was as beautifully unorthodox as her future work. She began with a degree in mathematics from the American University in Beirut, an education that gifted her a rare, abstract understanding of geometry. This foundational knowledge uniquely prepared her to conceptualize the complex, non-rectilinear forms that were once mere fantasies. It was at London's Architectural Association (AA) that her genius truly found its form, under the mentorship of visionaries like Rem Koolhaas. Here, she cultivated a profound fascination with the Russian avant-garde, particularly the Suprematist movement of Kazimir Malevich. She viewed painting and drawing not just as art, but as a "research principle" for "unlimited innovation"—a defiant rebellion against the "drab, cautious creeping time for architecture." This period of intense, painterly experimentation provided the conceptual blueprint for a career that would make her a visionary long before a single building stood in her name.

The Deconstructivist Ideology: Shattering the Box

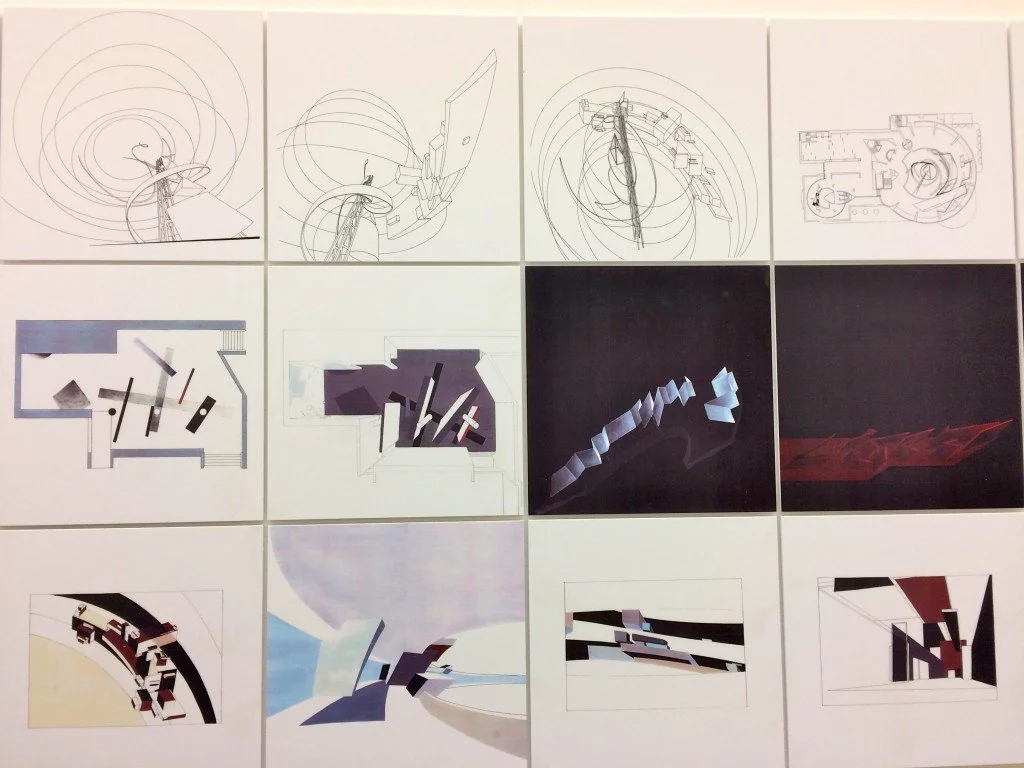

This image displays Zaha Hadid's visionary early architectural paintings. Created during her "paper architect" phase, these works served as a creative research principle for her deconstructivist style, exploring a new, fluid geometry long before it was possible to build.

Zaha Hadid’s architectural style is often classified under the banner of Deconstructivism, a postmodern movement she helped pioneer. This approach, characterized by a deliberate fragmentation of form and a joyful absence of traditional harmony, was a radical departure from the "ordered rationality" of modernism. Her work was a centerpiece of the seminal 1988 exhibition at New York's Museum of Modern Art, an event that helped introduce her to a global stage. Yet, to label her a mere Deconstructivist would be to miss the essence of her genius. For Hadid, fragmentation was not a philosophical end in itself, but a powerful tool to achieve a new architectural freedom. She saw it as an active process of "breaking the established guidelines" of traditional, "known illustrated architecture." Her work was a kinetic ballet, a study in dynamic fluidity that shattered the rigid, fixed notion of a single ground plane. In her own defiant words, "There are 360 degrees, so why stick to one?" This fundamental rejection of a priori constraints was the core of her quest, positioning her as one of The New Avant-Garde. By fusing the fragmented concepts of Deconstructivism with a "clear prevalence of fluidity and seamlessness," she created a new, third path in architecture—one that transcended the conventions of both modernism and postmodernism to become an art form of its own.

The Queen of the Curve: From Canvas to Concrete

For a significant portion of her early career, Zaha Hadid existed in the realm of the magnificent "paper architect." Her radical, color-drenched visions, though critically acclaimed, largely remained unbuilt, with competition wins like the Hong Kong Peak Club (1983) serving as a conceptual laboratory for her genius. This period was not a setback, but a foundational element of her legacy; as her mentor Rem Koolhaas once remarked, it would have been impossible for her to have a "conventional career."

The pivotal moment in her career was the dawn of advanced digital tools in the mid-1990s. While her vision for liquid, stretched, and organic forms had always been present on her canvases, the technology of the time simply could not render or construct these "complexities of compound curves." The shift to digital workflows was a direct and transformative liberation. The tools finally caught up to her long-held, visionary ideas, allowing her to realize the fluid and sinuous shapes that had always existed in her imagination. Her designs fostered a "strong reciprocal relationship" with technological innovation; her audacious visions pushed the development of new software and fabrication techniques, and in turn, those new digital possibilities inspired her team to "push the design envelope ever further." The once-unbuildable became not just possible, but a testament to her unyielding will.

Case Studies: Masterpieces in the Urban Fabric

The evolution of Hadid's philosophy is best understood through her seminal projects, each a powerful statement in a new architectural language. These masterpieces demonstrate her journey from a master of fragmented forms to a virtuoso of fluid, seamless urban landscapes.

Vitra Fire Station (1993), Germany: This was her first major built work—a dynamic, deconstructivist masterpiece forged in concrete. Its fragmented shell and angled rooflines served as a powerful physical declaration that her visionary ideas were indeed buildable, forever changing the expectations of what a structure could be.

Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art (2003), USA: This project marks a crucial transition, a magnificent bridge between her geometric style and her later fluidity. Its "Urban Carpet," a defining gesture where the public sidewalk "curves slowly upward as it enters the building," blurred the boundaries between the museum and the street, inviting the world in with a graceful, sculpted gesture. It stands as a testament to her legacy as the first American museum designed by a woman.

Heydar Aliyev Center (2012), Azerbaijan: Her ultimate expression. Considered her magnum opus, this cultural center is a study in pure form. Its seamless, "fluid form... emerges by the folding of the landscape's natural topography" with a complete absence of a single straight line. The design is a culmination of her influences, a lyrical blend of Arabic calligraphy and the spirit of historical Islamic architecture.

London Aquatics Centre (2012), UK: Built for the Olympic Games, its wave-like roof was inspired by the "fluid geometry of water in motion." This project showcased her ability to create a monumental, visionary structure that was both breathtakingly beautiful and deeply functional for its community long after the world stage had moved on.

An Enduring Legacy: A Force of Nature

Zaha Hadid's legacy extends far beyond her individual projects. She was a relentless trailblazer who shattered the glass ceiling in an industry long dominated by men. As the first woman to win the Pritzker Architecture Prize (2004) and the RIBA Royal Gold Medal (2016), she became a guiding light for a new generation of architects. Her fierce tenacity and unwavering self-belief, qualities that "took her to unprecedented heights," left an indelible mark on the world.

Her influence, however, is not a memory confined to the past; it is a living, breathing force that continues to shape our urban fabric. By pioneering the use of computational design, she bequeathed to the world a reproducible methodology, a powerful school of thought that her firm, Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA), carries forward with the same uncompromising spirit. Her architectural gestures—from the "Urban Carpet" to the seamless public spaces of the Heydar Aliyev Center—were physical manifestations of her belief that architecture could transcend mere function, shaping a more open, liberated, and democratic urban future. Zaha Hadid did not simply leave us with a collection of structures. She gifted us a new paradigm, a vibrant testament to the notion that the built world can be as fluid and as awe-inspiring as the natural landscape. In her boundless imagination, the future of architecture was not just designed; it was sculpted into being.

Authored by Christopher Banks, Anthropologist of Luxury & Critical Theorist. Office of Critical Theory & Curatorial Strategy, Objects of Affection Collection.