The Missing Mass: Gregory Sholette’s 'Dark Matter' and the Political Economy of Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art

This study establishes a critical theoretical link between Gregory Sholette's concept of "artistic dark matter" and the framework of Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art (PLCFA). It argues that the "state of exhaustion" characterizing the traditional luxury market is a direct consequence of its structural dependency on the vast, unacknowledged surplus of creative labor that Sholette identifies. Through case studies in fashion and art—including the appropriation of subcultures, the paradoxical career of Dapper Dan, and the commodification of protest aesthetics—this paper demonstrates how the luxury industry systematically mines "dark matter" for stylistic renewal, a process that hollows out meaning and creates the conditions for PLCFA's emergence. The study concludes that PLCFA can be understood as a "brightening" of this dark matter: a conscious codification of its inherent values (autonomy, non-market exchange, political utility) into a coherent framework of cultural resistance against the neoliberal logic of "bare art." By integrating Sholette's political-economic critique, this report reframes PLCFA not merely as an aesthetic shift, but as a vital political and economic counter-paradigm for 21st-century material culture.

Locating the 'Dark Matter' in the Post-Luxury Universe

The intellectual project of the Objects of Affection Collection is founded on the diagnosis of a paradigm shift in contemporary value: the emergence of Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art (PLCFA). This framework meticulously documents a cultural turn away from value systems predicated on conspicuous consumption and toward those defined by narrative depth, permanence, and an expanded sense of function. Concurrently, the artist and theorist Gregory Sholette has developed a powerful political-economic critique of the contemporary art world, centered on his seminal concept of "artistic dark matter". This study proposes that Sholette’s theory is the missing analytical key to understanding the structural forces that have given rise to the Post-Luxury phenomenon. The PLCFA framework, it will be argued, documents a cultural shift that is, in essence, the "brightening" of this dark matter—a moment when its long-suppressed values of autonomy, non-market exchange, and political utility become visible, coherent, and codified as a new system of value.

The analysis begins by drawing a direct parallel between the two crises identified by each theoretical framework. The PLCFA thesis diagnoses a "state of exhaustion" in the traditional luxury market, a system hollowed out by the "Scarcity Paradox" where mass expansion has destroyed the very rarity it purports to sell. This has untethered price from material reality, leading to consumer "price fatigue" and a "quiet rebellion" against logo-driven consumption. Sholette’s work, in turn, diagnoses a crisis in the art world driven by a neoliberal "enterprise culture," which systematically overproduces and marginalizes a vast surplus of creative labor in order to sustain a "winner-takes-all" market for a privileged few. These are not separate crises but two faces of the same structural logic. The PLCFA framework and Sholette's theory describe a single, unified political economy of culture from two different vantage points. PLCFA observes the symptoms at the "luxury" end of the spectrum—the hollowed-out value and the consumer's search for meaning—while Sholette diagnoses the cause at the "labor" end: the exploited surplus of creativity that the system simultaneously depends upon and renders invisible.

The 'dark matter' of creative labor: A vast, unacknowledged mass underpins the visible, traditional luxury art market, mirroring the iceberg metaphor for unseen support.

The emergence of PLCFA can thus be framed not as a simple change in taste, but as a material response to the conditions described by Sholette. The PLCFA emphasis on narrative, permanence, and expanded function represents a strategic move to reclaim the authentic value that is systematically stripped away by the mainstream cultural economy. If PLCFA is indeed a "brightening" of dark matter, then the Objects of Affection Collection is not merely a curatorial or critical project; it is an act of political economy. It is an attempt to build a new valuation system that recognizes and protects the creative labor that the mainstream system exploits and renders invisible, transforming the collection itself into a form of activist archiving.

The Political Economy of Invisibility: A Primer on Gregory Sholette's Core Theses

To understand the rise of PLCFA as a political and economic phenomenon, it is first necessary to establish the critical lens provided by Gregory Sholette's theoretical toolkit. His concepts offer the precise language required to describe the economic forces that have produced the cultural conditions to which PLCFA responds.

Artistic Dark Matter: The Unseen Engine of Culture

Sholette's central concept of "artistic dark matter" refers to the marginalized, unremunerated, and systematically underdeveloped aggregate of creative productivity that is nevertheless essential for the reproduction of the formal, mainstream art world. This "missing mass" encompasses the full spectrum of cultural production that exists in the shadows of high culture: the "makeshift, amateur, informal, unofficial, autonomous, activist, non-institutional, [and] self-organized practices". It is the vast ocean of hobbyists, failed art students, community-based collectives, and politically engaged practitioners whose creative output is deemed surplus or irrelevant by the official art market.

A visual archive of "artistic dark matter": Independent fanzines and self-published media from subcultures exemplify the vast, unacknowledged creative output outside mainstream institutions.

Crucially, Sholette's argument is not that the "light" world of high art is merely contrasted with this dark matter, but that it is structurally and parasitically dependent on it. This unseen mass constitutes a "shadow archive" of ideas and a vast consumer base for art supplies, magazines, and museum tickets. It also provides a reserve army of cheap, precarious labor—gallery assistants, art handlers, adjunct instructors—whose own creative ambitions fuel their willingness to work for low wages, thereby subsidizing the entire industry. The mainstream cultural economy requires this massive surplus to create the perception of scarcity and stardom for the few. The "failure" of the vast majority of artists is not an unfortunate accident of the market; it is a necessary, manufactured component of a system that runs on a "winner-takes-all" logic. Sholette’s aim is to "turn this figure and ground relation inside out," revealing the invisible labor that undergirds the visible spectacle. This analysis must also incorporate his vital clarification that dark matter is not inherently progressive or positive. As this invisible sphere "brightens" and becomes a more visible force, it can manifest as far-right or reactionary formations, not just pro-democratic ones, a nuance that is critical for avoiding a romanticized view of the "outside".

'Bare Art': The Logic of Neoliberal Enterprise Culture

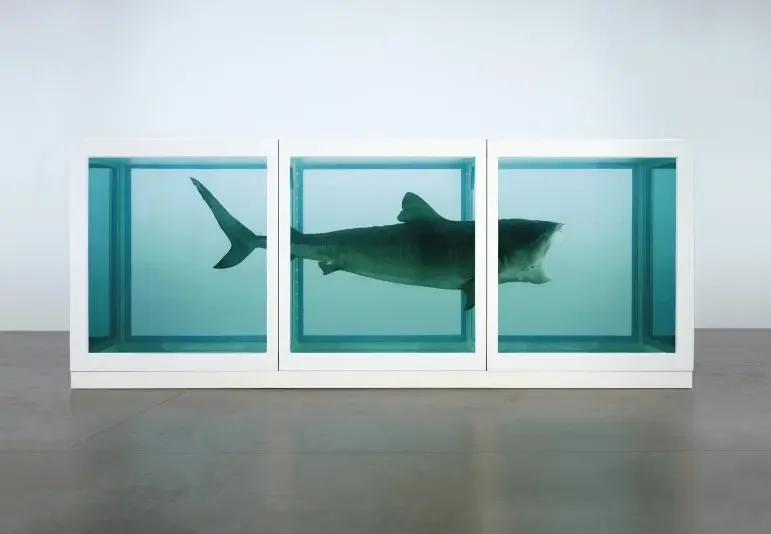

'Bare Art': Damien Hirst's preserved shark, stripped of traditional aesthetic autonomy, exemplifies art reduced to pure commodity status within a neoliberal enterprise culture.

To describe the condition of art within this system, Sholette introduces the concept of "bare art," borrowing from philosopher Giorgio Agamben's term "bare life". "Bare life" refers to a human existence stripped of political rights and reduced to a purely biological state. Similarly, "bare art" is art that has been reduced to its pure commodity status, stripped of any protective aesthetic autonomy by the logic of neoliberal capitalism. It is art that has been fully subsumed by capitalist modes of exchange, where its only function is to circulate within the flows of capital.

Sholette links this condition directly to the post-Fordist economic restructuring that has defined the neoliberal era since the 1970s, characterized by the financialization of markets, the flexibilization of labor, and the rise of precarity. In this "enterprise culture," all social phenomena, including art, are subjected to market logic. He describes the contemporary art world as an "indiscriminate maw perpetually opened in uninterrupted consumption," capable of assimilating any critique, any transgressive act, and turning it into another marketable asset. This concept of "bare art" provides a more potent and politically charged term for the "hollowed out" state of luxury described in the PLCFA thesis, a phenomenon explored in detail in "The Simulacrum of Luxury". It suggests that when a luxury object becomes a pure sign-value, detached from function or narrative, it has been reduced to a state of political and aesthetic nudity—a "bare" commodity whose sole purpose is to be exchanged.

The Artist as Activist: Resistance from Below

In response to the totalizing logic of "bare art," Sholette's work documents and champions a long tradition of resistance from below. He draws upon his own decades of experience as a participant in politically engaged artists' collectives—such as Political Art Documentation/Distribution (PAD/D), REPOhistory, and the Gulf Labor Coalition—to map a history of collective action. These groups represent a conscious effort to operate outside the market, utilizing "heterodox methods of organising" such as cooperative networks, non-market systems of gift exchange, and collective production.

His later work, The Art of Activism and the Activism of Art, further refines this analysis, defining the contemporary activist artist as one who uses "agitation and protest as an artistic medium". This practice, seen in the work of figures like Ai Weiwei, deliberately blurs the line between art and politics, challenging the very notion of aesthetic autonomy that "bare art" has already eroded from the other direction. Ultimately, Sholette's entire project is an attempt to construct a "political economy of the art world," shifting the debate on art's utility away from purely aesthetic concerns and "back within the domain of labour and value" where it belongs.

Activism as medium: Ai Weiwei's 'Sunflower Seeds' at the Tate Modern, composed of millions of individually handcrafted porcelain seeds, serves as a powerful political commentary on mass production, collective labor, and the individual's place in society.

The Cannibalization of Authenticity: How Luxury Feeds on Dark Matter

The mainstream luxury and fashion industries, facing a self-inflicted crisis of meaning, are structurally dependent on the periodic appropriation and commodification of the "dark matter" of subcultures and street styles. This process of cultural cannibalism reveals a system that cannot generate its own creative fuel, relying instead on a parasitic relationship with the very autonomous spheres it officially excludes. The constant cycle of appropriation is not a celebratory act of "influence" but a desperate act of survival, wherein the industry outsources its research and development to the unremunerated, invisible labor of subcultures.

From Subculture to Couture: Punk, Hip-Hop, and Skateboarding as Dark Matter Reservoirs

Subcultures are quintessential examples of Sholette's dark matter. They are autonomous, self-organized creative spheres that generate authentic styles, codes, and value systems outside of, and often in direct opposition to, the mainstream market.

The punk movement of the 1970s and 80s, for instance, forged its DIY, anti-establishment aesthetic from a working-class "trash" culture of necessity and political rebellion. Ripped clothing, safety pins, and subversive graphics were not stylistic choices but material expressions of an anti-consumerist, anti-authoritarian ethos. Designers like Vivienne Westwood initially served as conduits for this energy, but the aesthetic was eventually severed from its political roots, commodified, and sold by luxury and fast-fashion brands as a depoliticized "look".

Similarly, hip-hop fashion emerged organically from the urban Black experience in America, creating a unique visual language of aspiration, resistance, and identity. Initially, luxury brands were wary of this association, but as hip-hop's cultural dominance grew, they began to systematically co-opt its style, blurring the lines between street culture and high fashion and absorbing its hard-won cultural capital. The history of skateboarding culture follows a similar trajectory. It evolved from a rebellious, gritty counterculture with a distinct "anti-fashion" ethos into a major influence on global style, culminating in high-profile collaborations between skate brands like Supreme and luxury houses like Louis Vuitton. Each case demonstrates the same pattern: the "light" world of high fashion, suffering from a "state of exhaustion", turns to the "dark matter" of subculture for stylistic and narrative replenishment.

The culmination of subculture appropriation: The collaboration between skate brand Supreme and luxury house Louis Vuitton, where a rebellious subculture's aesthetic is fully commodified by the mainstream luxury market.

The Dapper Dan Paradigm: A Microcosm of Appropriation and Re-legitimization

The career of Daniel Day, the legendary Harlem designer known as Dapper Dan, serves as a perfect microcosm of this entire process. Operating outside the formal fashion system, Dan was an informal, self-organized creator who "blackenised" and "knocked-up" the logos of European luxury brands, creating a new, authentic, and highly influential style for a community that was explicitly excluded by those same brands. His work was a pure expression of dark matter creativity.

His story perfectly traces the cycle described by Sholette's theory. First, Dan's innovative practice thrived in the "dark," creating immense cultural value within his community. Second, the formal system attacked and suppressed him through legal action, with a lawsuit from Fendi forcing the closure of his boutique in 1992. Third, decades later, that same formal system—in this case, Gucci—facing its own crisis of authenticity as diagnosed in "The Luster Restored", "discovered" and appropriated his work, sending a nearly identical copy of a famous Dapper Dan jacket down its runway in 2017. Finally, after public outcry, the system re-legitimized him through an official collaboration, absorbing his powerful narrative of resistance to replenish its own symbolic capital. This case is not a heartwarming story of redemption, but a cautionary tale about the immense power of capital to rewrite history. The system that once criminalized Dan's practice now profits from his "authentic" story. This reveals that "narrative control"—a key pillar of the PLCFA framework—is the ultimate site of struggle. Gucci's collaboration was an act of purchasing not just a design, but a history of resistance that it could not generate on its own.

The 'Dapper Dan Paradigm': Gucci's 2017 runway look, a near-identical copy of a 1989 Dapper Dan creation. This act exemplifies the luxury industry's cycle of appropriating "dark matter" and later re-legitimizing it to absorb its narrative capital.

The Aesthetics of Poverty and Protest as 'Bare Art'

The logic of appropriation reaches its most cynical conclusion in trends that commodify the aesthetics of genuine hardship. Fashion trends like "homeless chic" or the "poverty play aesthetic" represent the ultimate reduction of lived struggle to "bare art". The visual markers of necessity and material deprivation—tattered, dirty, or ill-fitting clothes—are stripped of their material reality and sold as luxury commodities to the wealthy. This process, which Coco Chanel once termed la pauvreté de luxe ("luxurious poverty"), is a politically offensive "glamorization of poverty" that aestheticizes the very conditions it profits from.

The cynical commodification of hardship: Balenciaga's 'destroyed' Paris Sneaker, a prime example of 'la pauvreté de luxe' where the visual markers of poverty are repackaged and sold as a luxury good.

A similar dynamic is at play in the fashion industry's use of protest aesthetics. From feminist slogans printed on mass-produced t-shirts to runway shows staged to mimic protest marches, the visual language of dissent is frequently co-opted and commodified. In this process, the political function of protest is neutralized and transformed into a consumable style. This is a perfect example of the "indiscriminate maw" of Sholette's enterprise culture, which demonstrates its power by absorbing and selling back the very symbols of its own critique, a phenomenon also seen in the art activism of "The Secret Handshake".

The 'indiscriminate maw' of enterprise culture: Chanel's Spring/Summer 2015 finale, where models staged a faux protest. This event exemplifies the neutralization of political dissent, transforming the visual language of activism into a consumable, depoliticized style.

PLCFA as "Brightening" Dark Matter: A Framework for Resistance

If the luxury industry's primary mode of interaction with dark matter is parasitic appropriation, then Post-Luxury Conceptual Functional Art represents a conscious and strategic effort to make the inherent values of that dark matter visible, durable, and resistant to co-optation. The four pillars of PLCFA are not merely descriptive categories; they are active strategies of resistance. Each pillar functions as a specific tactic to counteract the economic and political forces that Sholette describes, providing a framework for how "dark matter" can protect itself as it "brightens."

This synthesis between Sholette's critique and the principles of PLCFA can be understood as an inherently political project. Sholette's concept of "Artistic Dark Matter" is precisely the unseen source of narrative value—evident in high fashion's reliance on street style—that PLCFA seeks to make visible and honor. The condition of "Bare Art" is what PLCFA identifies as the "hollowed out" sign-value of traditional luxury, a phenomenon exemplified by the cynical "poverty chic" trend and the commodification of dissent. In response, the political utility of "Activist Art" finds its direct parallel in PLCFA's insistence on the inseparability of concept and expanded function, as demonstrated by conceptually charged objects like the Vetements DHL shirt. Finally, Sholette's overarching critique of neoliberal "enterprise culture" is directly addressed by PLCFA's pillar of permanence over disposability, an ethos that aligns with the Slow Movement and a rejection of manufactured trend cycles.

The quintessential PLCFA object: The 2016 Vetements DHL t-shirt. By re-contextualizing a symbol of everyday labor as a luxury good, its primary "expanded function" becomes a political critique of value, branding, and the capitalist system.

Expanded Function as Political Utility

The PLCFA pillar of "the inseparability of concept and function" is a strategic move to re-embed objects with the political and social utility that "bare art" strips away. This aligns directly with Sholette's focus on activist art, where a work's primary function is to intervene, critique, or agitate in the social sphere.

A quintessential example is the Vetements DHL T-shirt from 2016. The "function" of this object is not simply to be worn; its primary utility is conceptual and political. By taking a ubiquitous symbol of global logistics and everyday labor—a piece of "dark matter" from the world of work—and re-contextualizing it as a luxury good with a luxury price tag, the shirt performs a critique of value, branding, and the arbitrary nature of the capitalist system itself. It is not an article of clothing so much as a piece of institutional critique in object form. Its function is to provoke a confrontation with the very logic of the system in which it circulates, making it a perfect PLCFA object whose highest utility is political commentary.

Narrative Control as a Shield Against 'Bare Art'

PLCFA's emphasis on "narrative control as a medium" is a direct counter-strategy to the condition of "bare art". By situating an object's value in an inalienable story, its ethical provenance, or the creator's specific philosophy, the PLCFA object builds a robust defense against being reduced to a mere commodity whose meaning can be easily appropriated and resold.

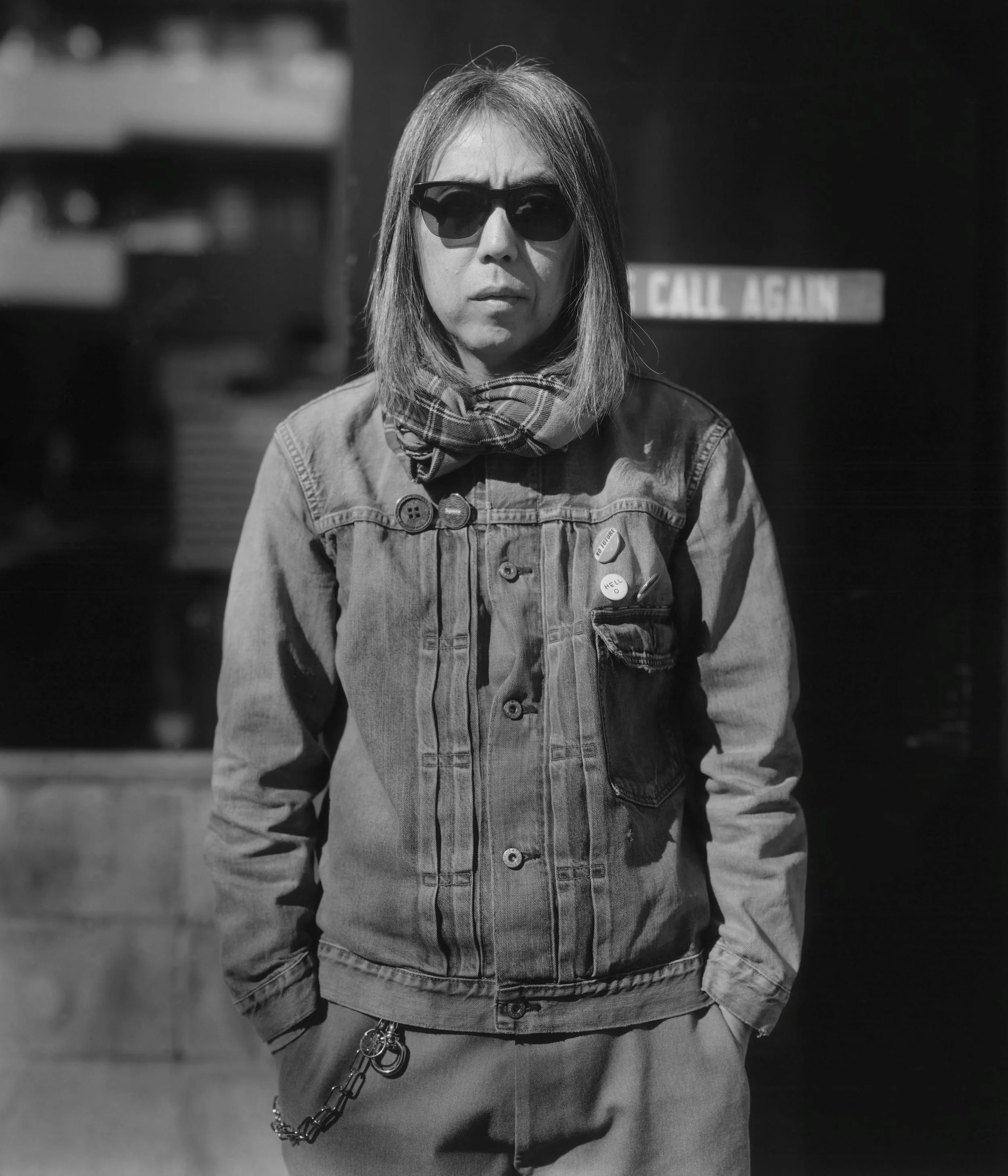

This strategy directly addresses the central problem highlighted by the Dapper Dan paradigm. If Dan had been able to maintain institutional control over his own narrative and the value it generated from the outset, he would not have been so easily excluded and later co-opted. The PLCFA framework, therefore, provides a model for creators to perform what the study on Mark Rothko called a "custodial strategy" over their own meaning. It champions the "Creator as Philosophical Architect," a role embodied by figures like Hiroshi Fujiwara, making their intention and intellectual labor the central, non-transferable source of value, thereby protecting the work from the hollowing-out effect of the mainstream market.

The 'Creator as Philosophical Architect': Hiroshi Fujiwara, whose personal philosophy and intellectual labor are the central, non-transferable source of his creations' value, shielding them from 'bare art' commodification.

Permanence and Stewardship as a Post-Growth Ethos

The PLCFA principle of "permanence over disposability" connects directly to the economic critique inherent in Sholette's work. Sholette's analysis of neoliberal "enterprise culture" is a critique of a system built on endless, accelerating cycles of production, consumption, and waste—a system that generates precarity for its workers and disposability in its products, a reality starkly contrasted by the collapse of narrative-driven brands like Brunello Cucinelli.

The PLCFA commitment to creating enduring objects that are meant to be "stewarded, lived with, and eventually passed down" is therefore not just an aesthetic choice but a profound economic one. It represents an implicit rejection of the growth-at-all-costs logic of late capitalism. This ethos aligns perfectly with the principles of the Degrowth and Slow Movements, which advocate for quality over quantity and intentionality over acceleration. A PLCFA object, in its very materiality and intended longevity, is a manifestation of resistance to the precarity and disposability that define the neoliberal condition for Sholette.

Towards a Political Economy of Affection

The integration of Gregory Sholette's theoretical framework provides the PLCFA thesis with a robust political and economic foundation. This synthesis demonstrates that the cultural shift towards PLCFA is not a superficial trend in consumer taste but a profound structural response to the deep contradictions of cultural production under late capitalism. Sholette’s analysis of "artistic dark matter" and "bare art" uncovers the hidden machinery of exploitation and commodification that produces the "state of exhaustion" in the luxury market that PLCFA first diagnosed. PLCFA, in turn, offers a coherent framework of resistance—a user's manual for how the values of dark matter can be made visible, protected, and codified.

This study moves the PLCFA project beyond a critique of aesthetics and into a more radical critique of cultural labor, value, and capital. The "affection" in "Objects of Affection" is revealed to be a political stance, an affection for authenticity, for meaningful labor, for permanence, and for community in the face of a system that commodifies, alienates, and disposes. It is an argument for a political economy of affection.

Authored by Christopher Banks, Anthropologist of Luxury & Critical Theorist. Office of Critical Theory & Curatorial Strategy, Objects of Affection Collection.